Tusket River & Basin

Introduction

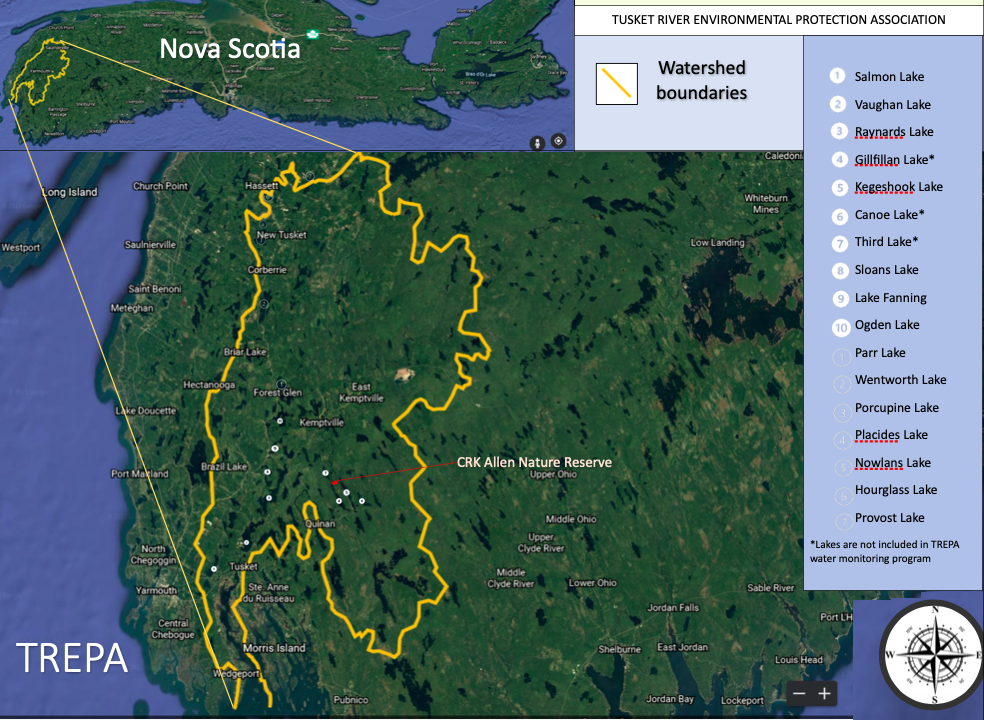

The Tusket River presents an area of 3000 square kilometres (1158 square miles) on the southwestern tip of Nova Scotia.

The area consists of a coastal basin with an inland watershed associated with the great Tusket River. This name is derived from a Mi’kmaq word “Neketaouksit” meaning “Great Forked Tidal River”. This unique and diverse environment has offered natural resources to the Mi’kmaq First Nation’s people for 7000 years and to the French Acadian settlers since the early 17th century. In the context of sustainable development, the present-day Acadians can offer a bilingual ecotourism package of nature-adventure and discovery blended with local history and heritage.

The following natural history of the area will be presented in two segments. The first section will describe the natural environment of the Tusket Basin and its interrelationships with the Acadian people. The second segment will describe the natural history of the Tusket River in a similar manner to present the Acadian in his natural environment.

Basin description

1. Physical features

The Tusket Basin has a width of 32 kilometres (20 miles) between headlands at Chebogue Point and Lower East Pubnico. The mainland coastline between these two boundaries is highly indented and irregular with a measure of 500 kilometres (310 miles). Elongated points, peninsulas, ridges, drumlins (low hills) and eskers are oriented North-South and are separated by many tidal channels, inlets, estuaries and bays. High tide in the estuary of the “great forked tidal river” (Tusket) carries salt water inland for 24 kilometres (15 miles). From the coast to the offshore there is an archipelago of 365 islands which are drumlins of various sizes.

A dominant feature of the Tusket Basin is the extensive area of salt marshes which occupy more than 8000 acres (3232 hectares), representing one third of the total salt marsh acreage in the province. These marshes are segmented by countless tidal channels, creeks, ponds and drainage ditches. Also visible at low tide are extensive areas of mud flats. These marshes and flats are associated with inshore islands and the indented coastline in the sheltered inlets, bays, channels, estuaries and tidal lakes.

2. Geology and vegetation

The soils of the marshes and flats are marine deposits of silt and sediment. A dense cover of salt water cord grasses grow on the marshes while the flats are sparsely covered by eel grasses. A few points and islands on the western and southern edges of the basin complex are glacial deposits of granite boulders. However most of the coastline and islands are drumlins of schist, slate or quartzite. The soils grow forests of white spruce, balsam fir, red maple, birch and aspen. Sheltered sites may have red oak and white pine. Black spruce and larch are found in swamps.

Some lands have been cleared for agriculture or to encourage the natural growth of blueberries. Many islands are forested by softwoods, while others are covered by grasses and/or shrubs. The forest has not regenerated on some islands that have become treeless due to fire or human harvest. Some larger islands have barrier-beach ponds, fresh water marshes and bogs. Some shores are lined with sandy beaches, boulders and rocky ledges where a variety of sea plants grow.

In the intertidal zone, between the high and low tide lines, floating rock weeds anchor to rocks while eel grasses grow on mud flats. This littoral zone is neither sea nor land but can be richer than either. This “edge” habitat is very significant in the Tusket Basin along the many islands and the extended irregular coastline. Beyond the low tide line, in shallow water that light can penetrate, mosses and kelp plants attach to boulders and rock ledges to form “marine forests”.

3. Water quality

Nutrients are carried to the Tusket Basin by fresh water flow from mainland rivers and brooks and by the salt water tides from the offshore to the coastal salt marshes. The basin tides are influenced by the adjacent Bay of Fundy which has the highest tides in the world. Most of the fresh water flows from the great Tusket River and from four smaller rivers (Chebogue, Little, Abrams and Argyle).

The fresh water flow meets the strong tides in the shallow basin studded with islands. The resulting turbulences, upwellings and mixing of nutrients create one of the most productive brackish- water environments in Nova Scotia. Dead plant matter (detritus) from leaves, cord grasses, eel grasses and sea plants is the nutrient base for marine life and productivity.

4. Fauna

Many wildlife forms are attracted to the diverse and productive habitats of the Tusket Basin. The salt marsh edges and the tidal creeks are especially attractive to fur bearers such as muskrat, mink, otter, raccoon, fox and coyote. Many inshore islands are visited by mainland species such as black bear and white-tailed deer. Hares, squirrels, grouse, small mammals, reptiles and amphibians inhabit most coastal islands. A few species of mice and snakes have managed to populate some of the offshore islands. The red squirrel, snowshoe hare, muskrat and ring-necked pheasant have been successfully introduced to some islands. The most numerous marine mammals are seals and porpoises.

The mud flats are invaded by migratory shorebirds in late summer. Mild winters and ice-free eel grass flats attract large flocks of over-wintering ducks and geese. The numerous peninsulas and large islands concentrate migratory song birds and hawks during the southward migrations of early fall. The offshore islands are famous for the many colonies of nesting sea birds such as gulls, eider ducks, cormorants, herons, petrels, terns, guillemots and puffins. A rare colony of roseate terns is described as the largest and most viable in Canada, representing one half of the entire Canadian population. The Atlantic puffin is also a rare nester in the Tusket Basin. Large raptors of the basin are summer nesting ospreys, over-wintering bald eagles and resident owls.

The most southern island (Seal) is renowned for its tremendous diversity of song birds and other bird species during spring and fall migrations. Exotic bird species often find refuge on this large island when they get stranded or disoriented during migration.

The intertidal zone and the marine forest of sea plants are especially rich habitats that are frequented by many invertebrates, mammals, birds and fishes of the Tusket Basin.

The basin fish life is exceptionally diverse. Species that migrate towards the rivers are salmon, gaspereau, shad, smelt, eel and the rare acadian whitefish. Estuaries and tidal lakes provide habitat for frost fish, striped bass and isolated oysters. One large tidal lake has distinct fish species. The most important fish in the food web of the salt marsh is the ” mummichog” minnow. The mud flats produce clams and blood worms. Rocky sea floors shelter an unsurpassed abundance of lobster, crabs and mussels. School of mackerel and herring abound to attract tuna, blue fish and “dog fish” sharks. Ground fish species include cod, pollock, haddock, halibut and flounder.

5. Human Relations

The First Nation’s Mi’kmaq people lived in this land for 7000 years. They subsisted mainly by hunting and fishing. With basic materials of wood, bone and stone they skillfully crafted survival tools such as canoes, snowshoes, arrows, spears, axes, knives, fish weirs and animal traps. Their hunting ability was enhanced by the use of hunting dogs.

The Mi’kmaqs were dependent on the seasonal availability and abundance of fauna. Many were nomadic between the coastal basin and the inland depending on the availability of clams, shellfish, sea mammals, salmon, eels, moose and fur bearers. Others were able to survive in permanent settlements at the head of river estuaries where high tide meets fresh water.

In the 1500’s, European fur traders and fishermen visited these shores. In 1604, explorers from France officially claimed and colonized this new land. A trading post was established to pursue the fur trade with the native people. One historical source suggests that this occurred in 1607 at Chebogue Point where a colony of French Acadians settled later. In order to succeed in the fur- trade and to acquire survival skills in this harsh land, the presence and cooperation of the Mi’kmaq people was essential. Reciprocal integration of Acadians and native people was a common practice.

The first Acadian settlers came to Chebogue Point with some knowledge of fishing and farming. The initial attractions of the fur trade were complimented by the rich fishing grounds. In 1690, Mr. de Saccardy reported that fishing in this area was the best in all of Acadia. When farm animals were imported for food and labour, life sustaining forage was required while the forested land was being cleared. The extensive salt marsh area (837 acres/343 hectares) along the Chebogue estuary provided a harvest of salt water cord grass (salt hay).

The Acadians became master builders of dikes and aboiteaux to reclaim salt marshes from the sea. These structures drained selected areas at low tide and prevented salt water inflow at high

tide. The resulting pasture or hayland was more nutritious than salt hay. Vegetables, grains and flax were also planted on these reclaimed marsh lands. Remnants of these structures are still present today. An antique aboiteau was recently discovered in the salt marsh silt and is presently displayed at the Acadian Museum in West Pubnico. The Acadians also made many drainage ditches on the natural salt marshes to improve their harvest of salt water cord grass. This salt hay was stacked on elevated platforms throughout the soft and wet marshes. This preserved the hay until winter when hard-frozen ground allowed its removal.

For nearly 150 years, the Acadian community survived and grew. An estimated 1000 inhabitants were spread along the Tusket Basin and beyond (Chegoggin to Cape Sable Island). Controversy with England brought about their deportation in 1756, 1758 and 1959. In 1767, after the Treaty of Paris (1763), some Acadians began to return only to find that most of their former lands had been granted to immigrants from New England called “Planters”. The persistent Acadian thus inhabited the less fertile lands on the many peninsulas and islands close to the fishing grounds. Farming became less important than fishing although salt marshes were still used to support farm animals until the 1960’s. Oxen and horses were required to harvest the forest for the building of fishing boats and sailing ships that traded around the world until the early 1900’s.

Today, the primary fishing industry places the many Acadian communities along the inlets, peninsulas and larger inshore islands that are interconnected by roads, bridges and causeways. When the infrastructure converted from boat travel to auto- roads, many small island settlements were abandoned. However many islands still have shanty complexes which are close to the fishing grounds and are inhabited by fishermen during the peak of the lobster season.

An infrastructure of approximately 40 public wharves are scattered along the basin coastline to provide access to the waters and shores. Many small wharves are in isolated areas that offer panoramic viewing, beach combing and bird watching. Large commercial wharves harbour fishing fleets and fish processing plants. The “shanty” islands have numerous private wharves that are lined with off-season lobster traps. Ecotour cruises are available to the many islands for experiences in lobster eating, shanty visiting, lighthouse and scenic viewing, seal and bird watching, geological and historical interpretation with information on island fishing and sheep farming. Sea-kayak tours are also available to provide nature-adventure amongst the coastal islands. Calm inlets and bays are accessed via passages with mighty tidal currents to provide a variety of kayaking experiences.

The present day fishing fleet is equipped with modern technology which diminishes the need for local lighthouses. The fleet is generally represented by numerous lobster boats with fewer herring seiners and ground fish draggers. Some of the vessels are the product of local boat building. Some boats have multiple uses by converting to gill netting, long lining, or the harvesting of sword fish and tuna. Other fisheries involve the harvesting of gaspereaux, clams, blood worms and sea plants. Aquaculture projects are also undertaken in the area.

Sports fishing for bluefin tuna was a major industry between 1935 and 1970. Wedgeport is now known as the Historic Sport Tuna Fishing Capitol of the World. A local museum commemorates this fact. Striped bass in the estuaries provide a summer sports-fishery. Occasionally bluefish invade the basin to provide an exceptional sports fishing adventure. Recreational fishing of

ground fish can be experienced by boat or from many wharves. The winter fishing for smelt and frost fish (tomcod) depends on ice conditions.

Another consumptive use of fauna by the Acadians involves the hunting of ducks, geese, deer, hares, grouse and pheasants along the coastal marshes, flats and islands. A few trappers harvest the fur bearers associated with the salt marshes. Non consumptive uses of this picturesque and enchanting environment include nature photography, animal and bird watching, beach combing, sunbathing, panoramic viewing, sea kayaking, island cruising, auto touring, biking, hiking and nature interpretation along designated nature trails and abandoned railway corridors.

6. Weather

The comfort of the local weather can be considered a unique attraction. Weather fronts travel west to east across the Atlantic ocean to reach the southwestern tip of Nova Scotia. The relatively constant temperature of the ocean produces cool air in the summer and mild air in the winter. Heat waves crossing the cooler ocean occasionally produce fog banks that cool the hot air. Comfortable sunbathing can be experienced at three area beaches. The area also features two golf courses.

7. Heritage

The ecotourist can experience the hospitality, friendliness and heritage of the bilingual Acadians by visiting the many communities of the Tusket Basin area. Adjacent communities have been isolated by the topography of the land and sea. A keen observer will notice that neighbouring communities have evolved distinctive characteristics of development, genealogy, appearance, language, food habits, fishing techniques and customs. Three summer festivals present opportunities for visitors to witness Acadian customs and heritage. Five museums present different themes of Acadian and local history. The Wedgeport museum presents the historical Sport Tuna Fishing Capitol of the World and other aspects of the fishing industry. In Tusket, Canada’s oldest existing courthouse and jail was built in 1804-1805. It presents historical aspects of government, genealogy and culture. The Catholic church in Sainte-Anne-du-Ruisseau presents the religious heritage of the Acadian people. Nearby Rocco Point is the historical site of the first chapel (1784) built in the area after the return from exile. A log style replica of this chapel commemorates the site. The Acadian Museum in West Pubnico focuses on genealogy and historical research. Another museum complex in West Pubnico replicates a historic Acadian village with restored old buildings that date back to 1832.

The area has many beautiful churches, old and modern houses, historical buildings, lighthouses, shipwrecks, monuments, tombstones, stonewalls, dikes and other structure of historical significance. At Chebogue Point, Louisiana “Cajuns” have recently returned to their homeland to operate the “Ferme d’Acadie” where visitors are welcomed to experience the tasting of manufactured cheeses and natural foods. The community of Little River claims the origin of a dog breed called the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever. This is the only registered dog breed native to Nova Scotia.

8. Infrastructure

This south western tip of Nova Scotia can be accessed via the Yarmouth Airport (only open to charter service) on the western border of the Tusket Basin. The CAT ferry links Yarmouth Harbour with the New England States. Two major highways leave the Nova Scotia capitol of Halifax to follow the western and southern boundaries of the province to terminate on the southwestern tip where the Tusket Basin is located. Many secondary roads are also part of the infrastructure. Detailed directions can be obtained from Nova Scotia Tourist Information Centres.

The numerous coastline communities are situated along the estuaries and on the many points, peninsulas and islands. They are all interconnected by auto-roads bridges and causeways that offer beautiful panoramic views. Communities on the ends of points and peninsulas are also linked by wharf and fishing boat access. The “shanty” islands can only be accessed by boat.

9. Accommodations

Accommodations and eating establishments can be found in the form of hotels, motels, bed and breakfast facilities, restaurants and shopping centres. A total of 900 rooms are available with the majority being located in the large centre of Yarmouth on the western boundary of the Tusket Basin. On the eastern boundary, the large village of West Pubnico also offers accommodations and services to tourists. Two major camping and tenting grounds are also found in the area.

River Description

1. Physical features

Five rivers and several brooks flow into the Tusket Basin. Little River and Abrams River can be better described as estuaries. The Chebogue River and Argyle River are larger with significant estuaries, however they only reach inland for 10 kilometres (6 miles) beyond high tide. The Tusket River (Great Forked Tidal River) is immense by comparison. From Wedge Point to Tusket Falls, the estuary is 24 kilometres (15 miles) in length. From the head of the tide, the Great Tusket River reaches inland for 93 kilometres (58 miles) to find its origin at Long Tusket Lake.

The main river and 10 branch rivers (forks) have a total length of 354 kilometres (220 miles) along the drainage of 176 lakes and countless brooks. All the rivers and brooks of the entire basin watershed drain a total of 213 lakes. Many lakes still retain Mi’kmaq names.

The main Tusket River flows North to South and generally divides the watershed into a western portion and an eastern portion.

2. Geology and vegetation (Western portion)

The main Tusket River and three western branches (Annis, Carleton and Wentworth) drain a landscape with a geological foundation of greywacke, quartzite, schist and slate. Gentle rolling drumlins impede the drainage to create sluggish streams with chains of elongated lakes. Meadows and bogs are also part of a landscape that exhibits excellent forest growth.

As part of the Acadian Forest Region, the forest is mostly represented by red spruce, hemlock and white pine with tolerant hardwoods on the top of drumlins. The tolerant hardwoods include sugar maple, yellow birch, beech and red oak. The lower areas grow black spruce, balsam fir, larch, red maple, white birch, ash and aspen. Some areas have been highly disturbed by clearing for agriculture. Some old fields are recolonized by stands of white spruce. Most of the old growth forest has been harvested but remnant stands still remain. Shorelines of lakes and streams may include coastal plain plants that are considered rare.

The main Tusket River is extended northwards by two branch rivers, the Silver and the Caribou. These two rivers drain an area where numerous granite boulders erratically cover the landscape. The granitic soils are shallow, leached and very acidic. The tree composition of the forest has a similar description as the main Tusket River area, except that unforested barrens and brushland semi-barrens are found.

3. Geology and vegetation (Eastern portion)

The geology and vegetative features of the main Tusket River extend for short distances into the eastern portion of the watershed. However, the upper reaches of three branch rivers (East Branch, Cold Stream and Quinan) drain a dramatically different landscape. Two secondary branches, the Napier and the Muskpauk, are also part of this eastern drainage.

The upper East Branch and the Napier River drain an extensive elevated plateau (400 + feet) of “Granite Barrens”. As the name implies, the bedrock is granite with a thin cover of loose, stony granite till. The landscape surface has no drumlins and is strewn with large granite boulders. Large areas of exposed bedrock can be found. Poor drainage has created many streams that flow between shallow irregular lakes, bogs, swamps and swales. On the border of the watershed, some lakes have beaches of white granite sand. The glaciers have formed long prominent eskers which are said to be the longest in the Maritimes.

This land is part of the Tobeatic wilderness area. This protected area (1000 square kilometres / 386 square miles) is the only remaining wilderness in Nova Scotia. The head waters of the East Branch are but a canoe portage away from the Shelburne River, the most remote wilderness river in Nova Scotia. This “Canadian Heritage River” links the Tusket watershed with Kejimkujik National Park.

The granite soils present a fascinating contrast in vegetation composition. Not only do they produce some of the most barren lands in the region, but they also support some of the most significant old forest stands. Along the river valleys, lake shores and islands, virgin and old growth stands of red pine, white pine and hemlock are exceptionally well developed. The barrens and semi-barrens (brushland) have a sparse scrub growth of white pine, black spruce, wire birch, aspen, red maple and red oak. Ground vegetation is dominated by a dense cover of shrubs such as huckleberry, holly, sheep laurel, viburnum and alder. On boggy sites, black spruce, red maple and larch are common.

The causes of barrens include deep repeated burns; excessive soil leaching causing low fertility; iron pans, excessive boulders and dense shrubs preventing tree growth.

The upper reaches of the Cold Stream and the Quinan River drain an extensive area of barrens and semi-barrens with a different geological foundation of quartzite, shale and schists. These barrens are mostly the result of repeated burning. The organic matter loss to fire has severely reduced the ability of soil to support good forest growth. The area features a few scattered drumlins and eskers with numerous lakes and a relatively unimpeded drainage.

The natural vegetation appears to have been white pine and red oak, but many hills only support scattered black spruce and low shrubs such as blueberry, sheep laurel and huckleberry. Ridges with deeper soils still support white pine and red oak with red maple and white birch. Low sites grow black spruce, balsam fir, larch and red maple. The shorelines and islands of Great Barren Lake and Quinan Lake still display old growth stands of red oak and mixed woods. This area is on the edge of a small isolated exposure of granite soils and boulders.

The Muskpauk tributary drains an area that is more typical of the coastline geology with ridges, drumlins and eskers of schist, slate or quartzite. Large sphagnum (peat) bogs have developed here with forest vegetation and barrens as described above.

4. Water quality

Most of the water of the Tusket River comes from run-off. Melting snows and rains provide maximum water flow during spring and autumn. Waters that percolate through the many peat bogs are stained brown by organic substances such as “tannins” that are naturally acidic. Acid rain increases the acidity since the hard rocks of the watershed yield very few buffering minerals. The productivity of these waters is generally very poor.

A few spring-fed clear water lakes are less acidic because they do not receive bog tannins and organic substances. The sunlight penetration allows plant life at greater depths. However the lack of organic substances render these clear waters less productive than the dark ones.

The drainage systems of the hard granite areas to the east are the least productive. In contrast the western branches of the Tusket River are the most productive since they drain more fertile soils.

5. Fauna

Large mammals of the watershed include moose, white-tailed deer and black bear. A remnant population of western Nova Scotia moose is associated with the brushland and semi-barrens of the Tobeatic Wilderness Area. The introduced white-tailed deer carried “moose sickness” and thus replaced the moose population in the more forested lands. A small herd of caribou became extinct at the turn of the century. Black bears are plentiful in the barrens and semi-barrens due to the abundance of berry- producing shrubs.

The snowshoe hare becomes exceptionally abundant during peak cycles in the brush and shrub lands where natural predators such as bobcats, hawks and owls also abound. Squirrels and chipmunks are mostly found in the forested areas.

The extensive areas of lakes and sluggish streams provide habitat for beaver, otter and mink. By the end of the 19th century, the Nova Scotia beaver was almost exterminated by over- trapping.

A remnant population survived in the remote parts of the Tusket watershed. In the 1930’s live beavers were captured and reintroduced to other parts of the province.

Inland muskrats are scarce, being more numerous in the fertile coastal marshes. Foxes and weasels hunt mice and shrews in the barrens, woodlands, old fields and marsh edges. Marten and fisher were recently reintroduced to the forested areas while the eastern coyote arrived naturally in the 1970’s. Past diseases have rendered the skunk a rare animal while the raccoon is abundant near human habitations and along the coast.

Game birds include the ruffed grouse in the woodlands and the introduced ring-necked pheasant along the coast. The Tusket watershed is renowned for migratory flocks of woodcock.

The waterfowl that reproduce in the inland wetlands include the black duck, ring-necked duck, wood duck, merganser and loon. The wilderness cry of the common loon can be heard around the many pristine lakes. A tremendous variety of smaller birds can be viewed in the diversified forest, brushlands and barrens edges.

The watershed has very significant spawning runs of gasperaux. A small run of atlantic salmon remains in the more fertile and less acidic branches of the Tusket River. The rare acadian whitefish may still exist. Acid rain and power dams have altered the former abundance of these fish. Speckled trout are found throughout in the less acidic and cooler waters. Shallow lakes with warm waters support white and yellow perch, bullheads, eels and several species of minnows. The introduced chain pickerel and smallmouth bass are well established in several lakes. The very acidic lakes only support tolerant eels and yellow perch.

Amphibians and reptiles are also found in the watershed. The rare Blanding’s turtle only occurs around the Kejimkujik Park area while painted and snapping turtle are common. All the snake species are non-poisonous.

6. Human relations

The Mi’kmaq First Nation’s people survived in this area for 7000 years by harvesting resources from the coast and the mainland. The “Great Forked Tidal River” provided canoe access to inland resources. According to Father Le Loutre (1748) the Acadians traded with the natives for beavers, otter, fox, marten, bear, wolf, wildcat, caribou and moose. He reported that this area (Cape Sable) was renowned for moose hunting and that “a quantity of eels so great as to fill ships” could be found.

The first Acadian settlers of the early 1600’s adopted many of the Mi’kmaq ways of survival. Some integrated with the native people. They certainly relied on canoe travel and river access to salmon, trout, eels, moose and fur bearers. Structural stone remains of eel weirs and moose pits can still be found.

The Acadian settlements remained coastal for 150 years. Then some Acadians escaped the deportation of 1755 by hiding inland with the native people. Others settled inland upon their return from exile. The communities of Belleville and Quinan were founded in the 1780’s. Quinan was originally known as the “Forks” as indicated in the Mi’kmaq reference to the Tusket as “the

Great Forked River”. In this area the Tusket River branches and many trails radiate from a traditional site called “Meat Rock”.

The Acadian farmers of Belleville and Quinan also utilized the forest. During winter, logs harvested by axe and saw were dragged onto frozen lakes by teams of oxen. The spring thaw provided flood waters in the rivers to float the “log drives” to water-powered saw mills.

In the 1800’s, wood products from the watershed were utilized in the ship building industry along the coastline of the Tusket Basin. Many of the sailing ships were captained by Acadians who traded lumber and other products all over the world. The traffic of merchandise included contraband liquor during the “rum running” days of prohibition.

The forest industry flourished all along the Tusket River. A historical operation was located on the Silver River near Long Tusket Lake. From 1895 to 1912, the Stehelin family from France established a remote self-sufficient colony that operated a saw mill complex. The lumber produced at “New France” was delivered to prosperous Weymouth by ox teams and by a steam locomotive on wooden rails. Thirty one years before electricity reached Weymouth, this remote colony was lit by a water powered dynamo. The Acadians called New France “The Electric City”. Restoration work has been undertaken at this historical site.

Many inland Acadians became skilled as “guides” for sportsmen in search of salmon, trout and moose. In the 1940’s and 1950’s, a population explosion of introduced white-tailed deer created a greater demand for hunting guides. Many traditional hunting camps still exist along the many trails of the watershed.

The numerous trails in the Quinan area have lead to many resources such as spruce “knees” for ship building; birch “hoops” for barrels; fauna for survival or sport; and berries for food. Many barrens were burnt to produce wildlife browse and commercial crops of blueberries. A historical blueberry site is called “Aggie’s Rock”.

Today, farming in the Tusket watershed is minor while the forest industry continues to be important. The history of mining relates to a few abandoned gold mines and a large inactive tin mine. A significant gaspereaux fishery and a minor eel fishery still exist on the Tusket River. Sport fishing, hunting and trapping are still valued as traditional activities.

Unmeasurable values can be attributed to the tremendous diversity and beauty of the landscape. The numerous pristine lakes and rivers offer private canoeing, kayaking and boating. Local guides are familiar with a diversity of canoe routes that offer white water and/or still water adventures. Spring and Fall canoeing are recommended in most rivers due to dry summer conditions. The entire watershed can be interconnected by long canoe routes that follow the down stream current. Shorter routes can be navigated during summer to visit old growth forests. The multicolors of the autumn leaves offer an exceptional aesthetic experience.

Some portions of the Tobeatic Wilderness Area can only be accessed on foot or by canoe routes and portages in very difficult terrain. Some lakes along routes have islands or shores with virgin forests and white sandy beaches. The Shelburne River (Canadian Heritage River) is the most remote and picturesque. The landscape is a contrast of lakes, still waters, granite barrens, eskers,

brushlands, meadows and virgin forests. This river provides a canoe link between the Tusket watershed and Kejimkujik National Park. The legendary “Jim Charles Rock” and “Junction Rock” are located in the habitat of a remnant moose population.

Some historical Mi’kmaq trails on long remote eskers remain relatively inaccessible in the Tobeatic Wilderness Area. Many of the traditional trails that radiate from “Meat Rock” have now been interconnected by users of all terrain vehicles. The entire watershed area has a tremendous potential for wilderness hiking and nature trail interpretation. Some sites like “Indian Look-off” and “French Hill” have beautiful vista views. The “old coach road” has an uncertain historical background. A few interpretive trails have been developed in the area.

The Tusket River watershed can treat the ecotourist to many nature-adventures such as nature photography, animal and bird watching, vista viewing, canoeing, kayaking, auto touring, wilderness hiking, biking, nature and historical interpretation with a blend of Acadian heritage.

7. Weather

Compared to the coastal weather, the inland climate is warmer in the summer and colder in the winter. Snow and ice accumulations become greater as the landscape elevation increases. Coastal fog banks rarely reach very far inland. Comfortable sun bathing can be experienced in isolated locations or on a lake beach at Ellenwood Park.

8. Heritage

The ecotourist can experience the Acadian heritage by visiting the inland communities of Belleville and Quinan. The friendly bilingual people are very hospitable. In the last century, Belleville was renowned for skillful craftsmen and carpenters. Well kept 19th century homes attest to this fact. The residents of Quinan are still known for their love of nature and their relationship with flora and fauna. This tradition was handed down by their forefather “guides”.

Quinan is the most inland Acadian community associated with the coastal Tusket Basin. Another Acadian community is found at Corberrie on the northwestern edge of the Tusket watershed along the Wentworth River. This village is however an inland extension of the large Acadian community of Saint Mary’s Bay.

9. Infrastructure

Access to the Tusket River watershed is via the infrastructure described for the Tusket Basin. The airport, ferry terminal and major highways connect with many secondary highways and access roads to reach inland and intersect many parts of the watershed. The western and eastern boundaries can be accessed by auto- roads. Highway #203 travels West to East to dissect the Tusket watershed into a southern and northern sections. The southern area contains the many trails that originate at “Meat Rock” near Quinan. Highway #203 forms part of the boundary of the Tobeatic Wilderness area in the northern section. The prohibition of motorized access is being considered for this protected area. Access may be restricted to foot trails and canoe routes. “Canoeable” waters are found throughout the entire watershed area.

10. Accommodations